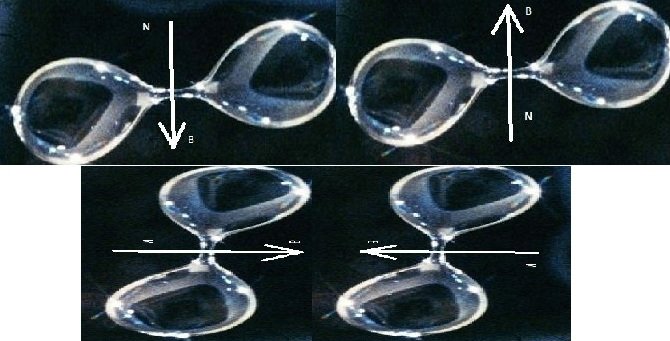

The pictures are unfortunate, although they somehow illustrate the descriptions in the note, but I don’t own computer graphics and I don’t have any programs for this either.

The upper one shows the particles “side by side”, rotating and magnetically attracted to each other.

The lower one is the frontal approach of particles with opposite magnetic moments and therefore repel each other.

Alas, the note, although popular, is purely physical and requires knowledge of some general points of physics.

I sincerely apologize to the readers who are unfamiliar with them! Moreover, there are many of my conjectures and hypotheses here, which, nevertheless, seem to me quite reasonable and adequate to reality.

I am always ready to explain and answer questions in a simpler and more popular way, if any, and if I can.

The preface and the afterword to the previous article “Problems of spin and magnetic moment of particles”.

Such charged and stretched droplets must lose rotational energy due to their rotation, radiating electromagnetic waves in the plane of their equator. There are several possible answers to this.

Yes, they emit waves into electromagnetic space and receive the same “recharge” from there, that is, long-lasting particles are durable not “by themselves”, but due to dynamic energy equilibrium with space: How much they lose, the same amount they get back. And those particles that “can’t do this” disintegrate! Decay!

In general, any unequally accelerated change in electric field strength (the third time derivative of electrical induction “D”) or accelerated changes in magnetic field strength (the second time derivative of magnetic induction “B”) cause electromagnetic radiation. So any wire with direct current must emit electromagnetic waves due to fluctuations in the density of the drifting electron cloud caused by the “scattering” of electrons on phonons and impurity defects of the lattice. Or as “Noise” in vacuum tubes, or during the magnetization and demagnetization of any ferromagnets, due to abrupt changes in the orientation of the electron spins in the domains. For some reason, no university textbook talks about this radiation, but the objective physical effect will not disappear from omission!

Another answer (according to Niels Bohr) is also rotation in “stationary orbits around its own axis.” Stationary means non–radiative.

The third answer is that there is no spin at all. And the magnetic moment is created by the existence of the electric entity itself, somehow pulsating and thereby creating a magnetic field.

The first two answers seem more plausible to me than the third one.

I’m getting to the point of the note.

Various combinations of charge, spin and magnetic moment of particles.

A pair of electrons.

The first option

Neighboring electrons. The left electron rotates from left to right, counterclockwise when viewed from above. Its mechanical moment of inertia (spin) is directed upward, but the magnetic moment due to the negative charge of the electron is directed downward.

The right electron rotates from right to left, clockwise, when viewed from above. Its mechanical moment of inertia (spin) is directed downward, but due to the negative charge of the electron, the magnetic moment is directed upward.

With such a mutual arrangement, both electrons are two elementary magnets, whose poles are counterdirectional and therefore they will be attracted to each other like two strip magnets with oppositely directed poles, despite the fact that due to the same sign of charges they will be electrically repelled. (A)

If you “push them together frontally”, and their spin and magnetic moment vectors are located ON the SAME AXIS, then in this case they will both electrically and magnetically repel. (C)

In such a pair, the total spin is zero, the magnetic moment is zero, and the charge is twice as large.

The second option

If the directions of the spins of both electrons are the same, then when placed “side by side, as in the figure, they will repel both electrically and magnetically. Two magnets with closely spaced poles of the same name. (A)

And during frontal approach, they attract magnetically and repel electrically. (C)

For such a pair, the total spin is one, and the magnetic moments and electric charges will also add up. That is, both the charge and the magnetic moment of the pair will be twice as large as that of a single electron.

Option three.

An electron and a positron with oppositely directed spins, that is, with oppositely directed vectors of the mechanical moment of inertia.

In this case, due to the difference in the sign of the charge, their magnetic moments will be directed the same way. This means that when placed “side by side”, they will magnetically repel, but electrically attract. (A)

In the case of their frontal approach, they will attract both electrically and magnetically. (B)

For such a pair, the total spin will be zero, the magnetic moment will be twice that of a single particle, and the charge will be zero.

Option four.

The electron and positron have unidirectional spins, that is, the vectors of their mechanical moment of inertia coincide in direction, and the magnetic moments are counterdirectional.

Then, when they are placed “side by side”, they will be two magnets with opposite poles, so they will be magnetically and electrically attracted to each other. (A)

In the case of their frontal approach, the multidirectional magnetic moments will cause their magnetic repulsion, with electric attraction! (B)

For such a pair, the total spin will be one, and the magnetic moment and charge will be zero.

Now let’s look at two real phenomena involving such pairs: Electron-electron and electron-positron.

Cooper pairs, which cause the superconductivity of some metals at cryotemperatures, and positronium, a pseudoatom without a nucleus in which an electron and a positron rotate around a common center of mass.

The following parameters are characteristic of a Cooper pair of electrons:

They are ATTRACTED to each other strongly enough to form a long-lasting pair (at temperatures below the “critical” for given metal). Their total spin is zero, which means that their magnetic moments are opposite directional. In the above options, this is option one (A). They are located side by side.

In the second case, they will also attract, but in this case their spin will be equal to one, not zero, as follows from the theory of superconductivity by Cooper, Bardeen and Schrieffer.

So, judging by the above, Cooper pairs are “two side–by-side, neighboring” electrons.

Moreover, their Coulomb repulsion is also strongly weakened by this arrangement, assuming that they rotate so that the “drop protrusion” of one electron falls perpendicular to the geometric center of the long axis of the “neighbor-partner”. Conventionally, for clarity, it can be imagined as two dumbbells, “two-headed matches”, as synchronously as two interlocked gears turning so that their axes turn out to be perpendicular to each other when the protrusion of one comes as close as possible to the geometric center of the other! Such rotation of electrons changes the forces of their electrical interaction, Coulomb’s law is violated in this case, because nominally, tacitly, it assumes the interaction of two charged spheres, charge points, conditionally.

And in this case, most of the charge is concentrated just in the “bulges” far from the geometric center of the particle. And, of course, when the bulge (half a drop) of one particle is located close to the geometric center of the other, where there is almost no charge, then their Coulomb interaction is noticeably less than if both particles were charged balls with three-dimensional symmetry of the charge arrangement.

In my opinion, this is an extremely important physical factor that REDUCES ANY electrostatic interaction of particles (both attraction and repulsion), if, of course, we allow for such an “elongated droplet structure” of electrons, positrons and other charged particles.

It is possible that even with the frontal approach of both particles, their rotation is “synchronized” in a peculiar way. For example, since the two “bulges” of electrons carry the same charges, they will repel each other and take a cross-shaped position. Option two (B)!

If the electrons were just charged balls, then, of course, such an effect simply could not exist, but with the proposed hypothetical view of the “elongated droplet structure” of elementary particles, this is quite likely.

Positronium exists in two states, parapositronium, when the spins of the electron and positron are antiparallel, and orthopositronium, when they are parallel. Interestingly, the “lifetime” of both is very different. Parapositronium annihilates after 1.25 ten-billionths of a second, and orthopositronium “lives” a thousand times longer and annihilates after 1.4 ten-millionth of a second! This is most likely caused by a difference in the orientation of the spins. In parapositronium, an electron and a positron are attracted to each other due to electric (Coulomb) forces and due to magnetic mutual attraction. Option three (B), option four (A), but here the electric attraction is weaker than in the frontal approach of an electron and a positron, in accordance with the last remark in the paragraph describing Cooper pairs.

In orthopositronium, Coulomb forces of attraction act, but also strong magnetic repulsion. Option four (B).

Faciant meliora potentes.

If I’m wrong, let my seniors correct me.

28 VIII 2025